mikeb and I were discussing the papers given at BioConcur the

other day, and we were puzzling out the differences between the

standard way of modelling biochemical and biological reactions

(including genetic interference reactions) and our “alternative”

modelling style. I suppose the “alternative” style must have been

tried before, and that it must display some obvious weakness we

haven’t spotted yet.

Here’s a comparison of the two styles:

| Biological Systems Element |

Standard Model |

"Alternative" Model |

| Molecule | Process | Message |

| Molecule species | — | Channel |

| Interaction Capability | Channel | Process |

| Interaction | Communication | Movement (and computation) |

| Modification |

State and/or channel change |

State and/or channel change |

| Reaction Rate |

attached to channel |

attached to prefix |

Join and Rates

We’ve been thinking about using a stochastic π-variant with

a join operator. Having join available allows the expression

of state machines to be much more direct than in a joinless stochastic

π. We started modelling the lambda-switch to fit the model from this

BioConcur paper, and saw that it seems more natural to attach the

reaction rate to each individual join rather than to each channel as

BioSPI does.

Bisimulation

The standard model has comm meaning interaction; we have comm

meaning movement in some sense: atoms (mass) move from one

locus (molecular species) to another, or a molecule undergoes

conformational change, which is a kind of motion from one state or

class or species to another. This means that bisimulation in the

alternative model has to do with movement rather than interaction

— which seems more fine-grained, but perhaps less natural.

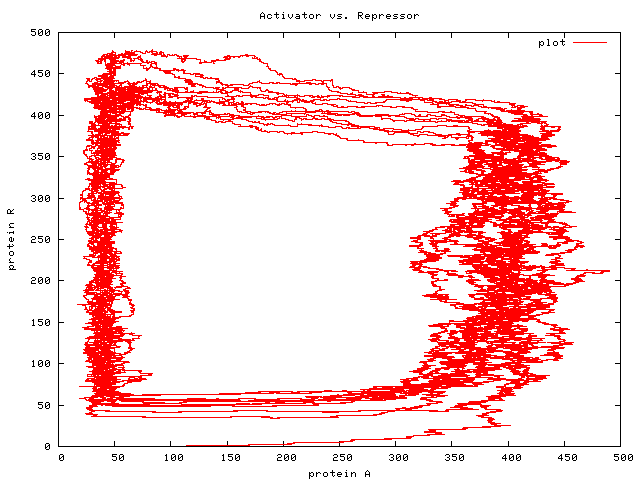

Uncertainty in Biological Simulation

We also thought about a few properties biological simulation

systems ought to have. One important one is a notion

of uncertainty. Few of the current systems are honest about

their limits — only one of the papers at BioConcur displayed

error bars on any of its graphs! The systems in use all generate

probable trajectories through state-space, and this is I assume

implicitly to be understood by the reader of the various program

outputs, but it would be useful to have the uncertainty in the results

reflected in the various displays that these systems produce.

Besides the uncertainties that come from stochastic modelling and

Monte-Carlo-type approaches in general, all the inputs to the systems

(eg. rates) are purely empirical data, with associated uncertainties,

and these uncertainties are not propagated through the system. Not

only do the outputs not show the variation in results due to random

sampling, but the outputs do not explore the limits of the accuracy of

the inputs, either.

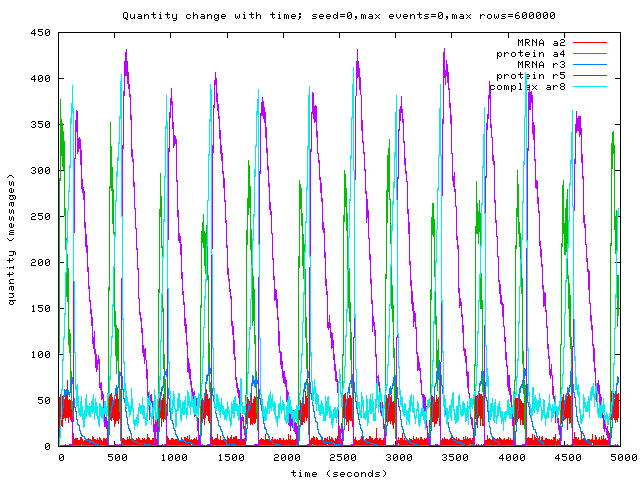

Reagent concentration vs. Gillespie vs. Modelling reagent state

The alternative model deals well with high reagent concentrations,

since a high concentration is modelled as a large number of messages

outstanding on a channel. The Gillespie scheduling algorithms are

O(n)-time in the number of enabled reactions, not in the

concentrations of the reagents. The standard model suffers here

because each molecule is modelled as a process — that is, as an

enabled reaction. In a naïve implementation, this makes the scheduling

complexity O(n)-time (or at best, O(log(n)) time if the

Gibson-Bruck algorithm is used) in the number of molecules in the

system.

However, modelling molecules as processes seems to provide one

advantage that doesn’t easily carry over into the alternative model:

molecule-processes can involve internal state that any interacting

molecule need not be concerned with. For example, enzyme-private

channels with different rates associated with them might be used to

model the different reactivities of phosphorylated and

unphosphorylated states of the enzyme.

Perhaps a hybrid of the two models will be workable; after all,

even in the alternative model, you have the freedom of the restriction

operator available for implementing complex behaviours. The

alternative model allows some common patterns to be expressed more

simply than the standard joinless model though, it seems.

We’re still thinking about ways of keeping the

molecules-as-messages approach while allowing reactions to specialise

on molecule-message state or to ignore it, as appropriate.

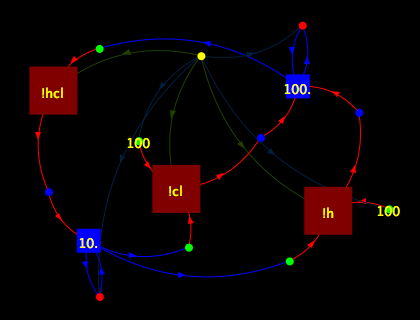

Compartments

BioSPI 3.0 took the standard stochastic-π implementation and added

BioAmbients to it (see the 2003 paper by Regev, Panina, Silverman,

Cardelli and Shapiro). Any stochastic-join will probably benefit from

being able to model compartments similarly.

The simple, ambientless approach suffers some of the same problems

as SBML is facing with regard to recognising the similarity of species

across compartments. Some way of factoring out reactions/processes/etc

common across all compartments should be useful.